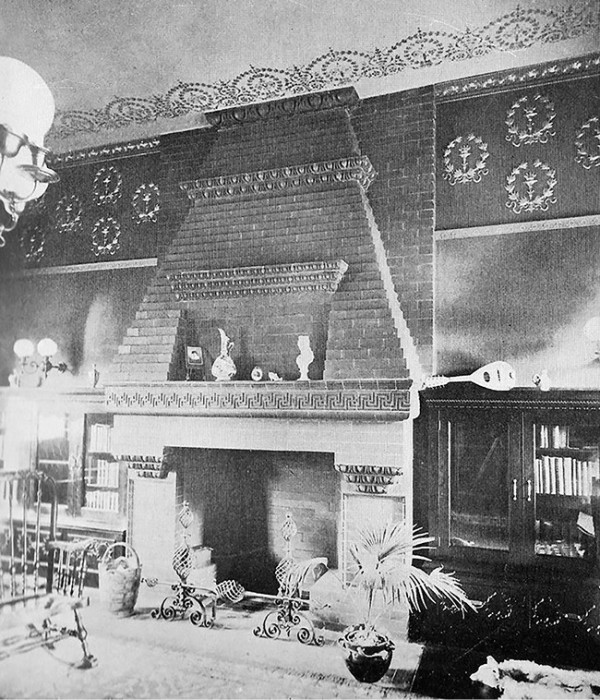

Sketch No. 4 Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book, 1904, ornamental face brick produced by the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company incorporated into a fireplace design.

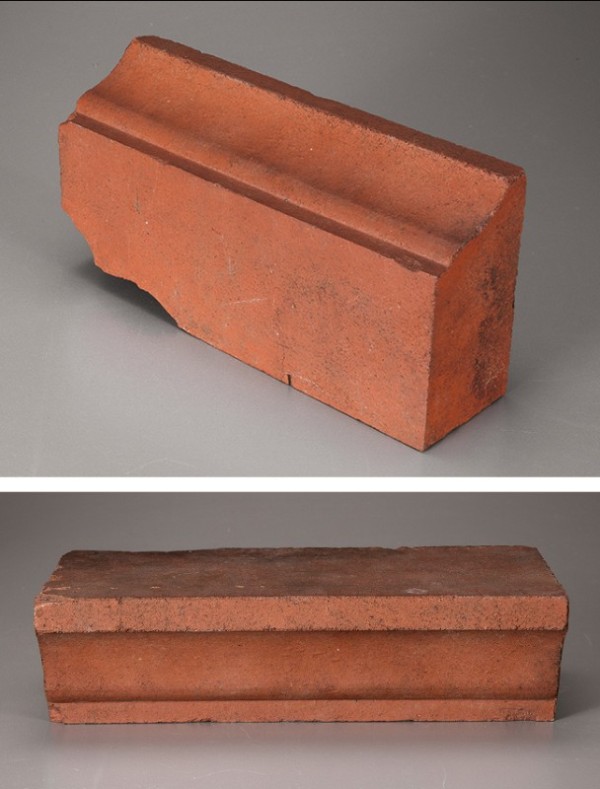

Ornamental face brick, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Milltown, New Jersey, 1887–1904. Earthenware. Excavated from the former factory site in the 1990s. (Unless otherwise noted, photos by Robert Hunter.)

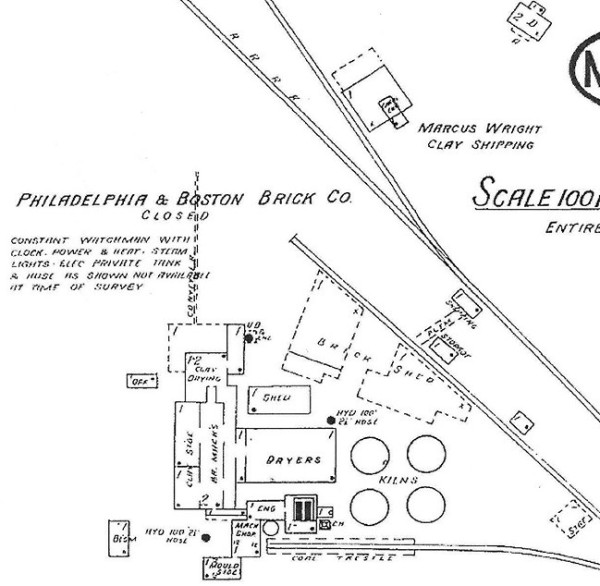

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Milltown, New Jersey, 1924. Although grouped with the Milltown Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, the Philadelphia and Boston Brick Company was situated in East Brunswick along the Raritan River Railroad. Note the “conveyor” running from the clay drying building near the top. The open area around the conveyor may have been the clay pits, and is where many of the waster bricks were discovered.

Molded face brick, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company. Milltown, New Jersey, 1887–1904. Earthenware. Excavated from the former factory site in the 1990s.

Molded face brick in the guilloche design, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Milltown, New Jersey, 1887–1904. Earthenware. Excavated from the former factory site in the 1990s.

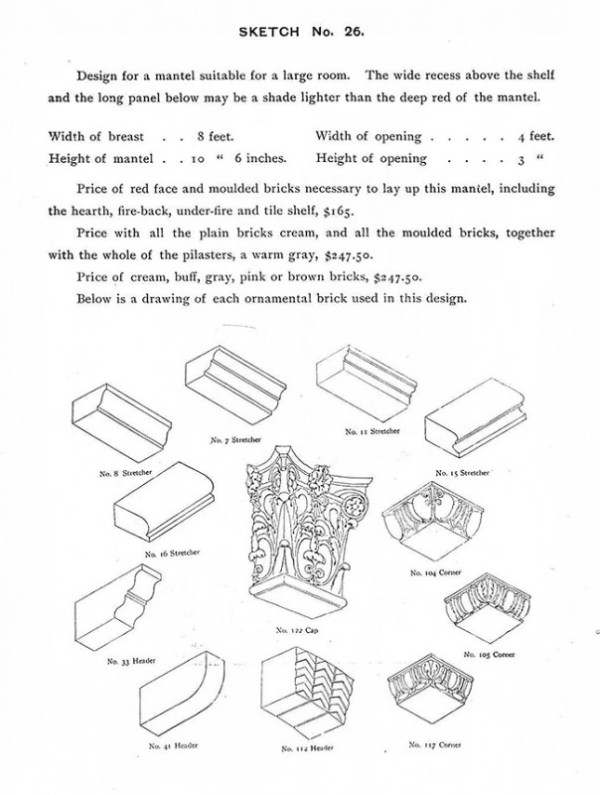

Sketch No. 26, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904.

Sketch No. 12, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904. The design is adapted from a “mantel frequently seen in England and France, with a hood extending to the ceiling.”

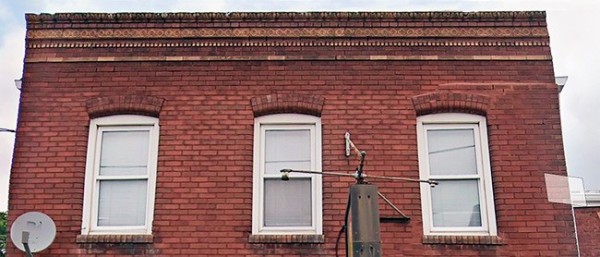

Commercial building at 61 Whitehead Ave., South River, New Jersey, with a decorative cornice of ornamental face brick.

Photograph taken in 1988 showing the ruins of the former factory site. (Photo, Mark Nonestied.)

The former site of the Philadelphia and Boston Brick Face Company prior to redevelopment in the 1990s. Note the large piles of waster bricks that recently had been uncovered during environmental trenching. (Photo, Mark Nonestied.)

Waster bricks uncovered in the 1990s during redevelopment of the property. Many exhibited firing imperfections such as cracks, spalling, and fusing. The three examples below the trowel are fused together. (Photo, Mark Nonestied.)

Waster bricks just below the surface. (Photo, Dawn Turner.)

Waster bricks, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Milltown, New Jersey, 1887–1904. Earthenware. Excavated from the former factory site in the 1990s. These examples show the range of colors, including red, buff, and mottled gray.

Egg-and-dart brick wasters, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Milltown, New Jersey, 1887–1904. Earthenware. These pieces were fused together by the heat of the kiln.

Grossly overfired bricks, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Milltown, New Jersey, 1887–1904. Earthenware.

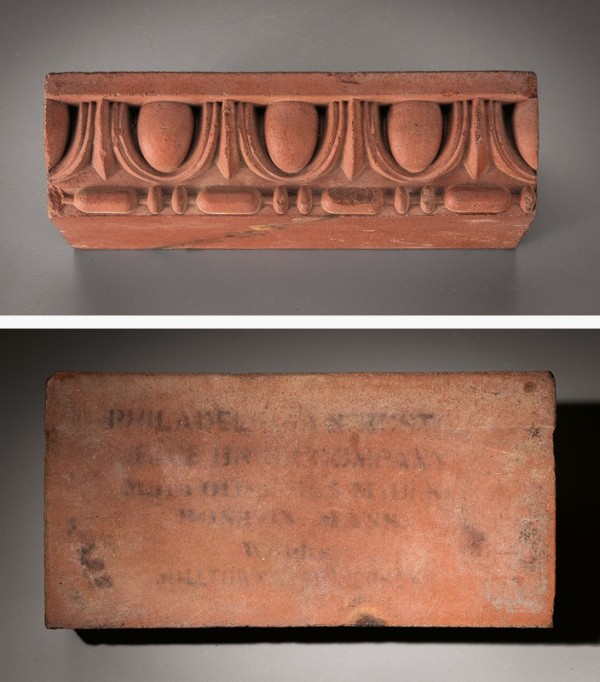

Waster brick above and detail below of waster brick recovered from the former factory site showing a stenciled factory label, the only example recovered. “Philadelphia & Boston / Face Brick Company / [Main Office 165?] Milk [St?] / Boston Mass / Works / Milltown.”

Test tile, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Milltown, New Jersey, 1887–1904. Earthenware. Excavated from the factory waster pile. (Photo, Mark Nonestied.)

Face brick, a high-quality brick often utilized for the facades of buildings, has received little scholarly attention in the ceramics field, yet its use brought texture and color to interior and exterior ornamentation during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When pressed into molds, such decorative elements could be replicated for use in fireplace mantels, cornices, window moldings, and more. This article hopes to shed light on this industry and the products it produced in the hope that it will lead to a greater appreciation for this under-appreciated form of decorative architectural ceramics.

Middlesex County, located in central New Jersey, is home to the Raritan Clay Series, a deposit of clay that “forms a broad belt, extending from Raritan Bay across the state to Trenton and Bordentown.”[1] The county was given extensive coverage in George Cook’s 1878 Geological Survey of New Jersey: Report on the Clay Deposits of Woodbridge, South Amboy and Other Places,[2] and in 1904 geologists Heinrich Ries and Henry Kummel further noted its significance to the clay industry by stating that Middlesex County “is the most important clay producing county in the State of New Jersey.”[3]

The ceramics history of Middlesex County can be traced to the late eighteenth century, when potters like James Morgan began utilizing local clay for the production of stoneware.[4] The industrialization of this cottage industry occurred in the mid-nineteenth century, when Middlesex County became the hub of a thriving ceramics industry. The clay industry supported countless local ceramics factories, including those that produced bricks, tiles, and terracotta. By the end of the Second World War, the ceramics industry had left the region, and today none of the factories that once defined the region is in operation. Materials produced in those factories, however, can still be seen today as, for example, architectural elements on buildings or ceramic gravemarkers in local cemeteries.[5] The opposite can be said for the places where clay was transformed into product. Most of the manufactories have vanished, but as development transforms the last vestiges of an industrial landscape for modern use, remnants of a bygone era are uncovered. Among the numerous factories operating within the clay district was the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, a business that specialized in plain and ornamental face brick for both interior and exterior applications. This paper will explore the history of the factory, the use and production of face brick, and the discovery of an enormous waster deposit at the site of the former factory.

The Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company was initially a Boston- based operation with an office at 4 Liberty Square and a factory at 455 Medford Street (other references note 425 Medford Street).[6] The company was in operation by 1887, having set up a display at the Sixteenth Triennial Exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association from September to November of that year. Their exhibit of “face, pressed, and moulded brick” in “many new and beautiful designs” won them a silver medal.[7] By 1889 the company had printed a trade catalog of plain molded and ornamental brick, and its factory on Medford Street had the ability to produce 48,000 bricks a day, 15,000,000 bricks annually (fig. 1).[8] Production continued in Boston through the early 1900s, although by 1904 the company office had moved to 165 Milk Street.[9] In 1910 manufacturing operations were started in East Brunswick, New Jersey, where the company purchased land from Emma Warnsdorfer, Milton Edgar, and the Edgar Bros. Company.[10] The Edgars were in the clay business with property in Woodbridge and to the west of South River, where Milton Edgar owned clay pits. The company was mining clay and shipping it to factories.[11] The Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company purchased its buff and cream burning clays from New Jersey and its red burning clays from Maine and Massachusetts.[12] Milton Edgar’s pit had the buff burning clay, but it is not clear whether a relationship with the Edgars existed prior to the purchase of property from them. By the late nineteenth century there had been a shift in taste from red face brick to other colors of buff, mottled, and speckled (fig. 2). Central New Jersey became the ideal location because of its supply of buff burning clay. Other ceramic producing areas of New Jersey, such as Trenton, supported an early face-brick industry utilizing local deposits of red burning clays. By 1894 the Trenton face-brick industry had declined, and continued to do so into the early 1900s as other colors became popular.[13] While most ceramic factories were centered in urban areas or became the nucleus of a town, the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company was unique in its location. Situated in rural East Brunswick, the factory was essentially an industrial island in a sea of farmland. The factory was well placed along the newly constructed Raritan River Railroad, which provided an east-west route from New Brunswick to South Amboy, where it connected to a larger rail line. Edlow Harrison, an investor and civil engineer from Jersey City, envisioned that the railroad would “run directly through the clay lands of the Raritan Meadows between South Amboy and Washington [today South River], and spurs will be built to the brick yards.”[14] The line to New Brunswick was completed by 1890 and indeed numerous ceramic and clay concerns took advantage of the direct rail connection. The Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company was among the factories serviced by the Raritan River Railroad. There were two sidings from the main line that accessed different parts of the factory. In addition, a shipping building and platform were located directly on the main line. By 1912 the East Brunswick operation employed sixty people and a company trade catalog from 1917 included no reference to the Boston factory, only the one in East Brunswick.[15] The 1918 New Jersey Industrial Directory indicates that the East Brunswick operation employed only ten people; the following year the property was repurchased by the Edgar family at a sheriff’s sale.[16] The company ceased operations altogether by 1924; that year the factory buildings were included on a survey for a Sanborn Fire Insurance Map and recorded as “closed” (fig. 3).[17] Note the “conveyor” running from the clay drying building near the top. The open area around the conveyor may have been the clay pits and is where many of the waster bricks were discovered.

The face brick produced by the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company was a type of high-quality finishing brick, as opposed to common brick with its rough and imperfect surface. The company also specialized in decorative brick, both “plain moulded” and “ornamental.” The plain molded assortment was produced in a variety of different molding styles, whose designs included bull nose, cove, and beaded (fig. 4), and each was assigned a design number from 1 to 99.[18] The ornamental bricks were embossed with architectural features that included, among others, metopes, scrolls, guilloche, Greek keys, and egg-and-dart, bead-and-reel, and rope molding. Some of the designs were available in small and large sizes (fig. 5) and were assigned numbers from 100 to 200. Design number 122, a Corinthian “Cap,” was the most ambitious as it resembled a product generally associated with an architectural terracotta company. The company also produced at least two geometric tile designs, numbers 300 and 301, that were meant to interlock and create larger mosaic patterns.[19] In addition to headers and stretchers, these products were also available as returns and corners, enabling the design to terminate into a feature or be carried around a corner. With those options, any combination could be used to create cornice work, pilasters, projecting mantels, moldings, or niches. If surviving trade catalogs are any indication of the primary use of the finished products, then fireplace mantels clearly dominated. Trade catalogs from the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company in the collection of the Avery Library at Columbia University testify to the importance of fireplaces. The company’s first “sketchbook” with mantel designs was issued in 1891; by 1895 the demand had grown so fast that the company increased the number of designs offered in its sketchbooks.[20] By 1904 the company catalogue was offering fifty-nine designs ranging in price from $12 to $247.50—design number 26 was the most expensive and included Corinthian capitals framing the fireplace (fig. 6). The factory produced bricks in various colors, red being the most inexpensive. Colors of cream, buff, and gray bricks were also available at higher cost.[21] A number of factors aided in the growth of the company, among them an expanding housing market, the increasingly widespread use of bricks as a construction material, and the popularity of colonial revival architecture at the close of the nineteenth century. Brick was a natural choice for the construction of fireplace hearths, but a case had to be made to replace wood mantels with those of decorative brick. The company stated in their catalogues that brick mantels were the latest trend and that wood mantels were a “practice which is now passing by.”[22] The use of too much woodwork in a room was also deemed unacceptable by the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, which declared it made the room feel “crowded in,” whereas “having the Fireplace Mantel entirely of brick obviates such a defect.”[23] The company’s marketing seemed to focus on the use of heavy woodwork, and one should not “overcrowd the eye with a mantelful more.”[24] Late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century fireplaces were commonly faced with glazed bricks and tiles, another hurdle the company had to overcome. Trade catalogs implored that glazed bricks and tiles were not adequate because they had a “cold and glassy effect,” unlike bricks which “have a soft, rich, and resting effect.”[25] The colonial revivalism of the late nineteenth century helped to reintroduce the fireplace as a focal point of the home, and this was emphasized in the company’s marketing: “the fireplace has always been, and always will be, the happiest rallying-place of the family”; it has been aptly called the “sun in the house”; and home builders should consider having “one or two open fireplaces.”[26] Some of the inspiration for the fireplace designs came from England and Europe. The plans were “all prepared by a well-known Boston architect whose extended European travel rendered him peculiarly fitted for the work, and the designs embody many of the best ideas of the best brick work of England and the Continent” (fig. 7).[27] The fireplace trade seemed so lucrative for the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company that it diversified its product line by including fireplace accoutrements. In 1905 the company produced a trade catalog devoted to fireplace furnishings to accompany its brick mantels. A wide variety of fireplace accessories were included, such as andirons, ash dumps, ash pit doors, dampers, fenders, fire screens, fire sets, gas logs, gas grates, grates, jamb hooks, portable fireplaces, and spark guards.[28] Although surviving trade catalogs and advertisements illustrate only the interior applications of face brick, the designs seem to have been utilized for exterior building ornamentation as well. Middlesex County has a number of commercial brick buildings that used ornamental brick for their facades. Some notable examples can be found on State Street in Perth Amboy and Whitehead Avenue in South River (fig. 8). The ornamental bricks on those buildings are identical to what were available through the company’s trade catalogs. Although primarily utilized on the front facades of commercial buildings, two unusual folk architectural examples have been documented in Middlesex County. In North Brunswick, at 929 Hermann Road, a one-and-a-half-story home incorporated ornamental brick as a belt course. The body of the house is a buff-colored face brick that might have been produced by the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company. In the borough of South River, at 280 Old Bridge Turnpike, is a brick home that placed ornamental brick for window details. A large version of the egg-and-dart molding was installed as a windowsill. Chevron designs were also used in an arch above the window. The unique folk style of these two houses and the fact that both are within a few miles of the factory site seem to indicate a special connection to the company that certainly deserves further research.

The production of pressed brick originally took place in the Boston factory of the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company. In 1910 the company moved its operations to East Brunswick, where it had several one- and two-story buildings, including an office, brick sheds, a mold storage room, drying rooms, an engine room, and four kilns.[29] The factory was laid out in such a way as to ensure a smooth flow from raw clay to finished product, with each operation nearest the previous production procedure. The clay might have been supplied from the property, where a conveyor belt would have carried the material directly from clay pits into the building where it was processed, and then placed into storage bins.[30] Adjacent to the clay storage rooms was a two-story building that contained the pressing machines. The close proximity of the engine room would indicate that the machinery was operated by steam-powered line shafts. The Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company utilized steel molds for its bricks, a material that allowed for sharp, clear designs and corners. Face brick was molded by either a dry, semi-dry, or re-pressing process.[31] The dry and semi-dry processes are similar in that the moisture content determined the molding method. In both methods the pressing process would drive out any remaining water. Ries and Kummel remarked that the pressing equipment for this method was expensive, although the cost could be negated because in using this process the factory did not need to construct the dryers that would have been necessary with the re-pressing method.[32] Another method of producing face brick, which seems to have been the one utilized by the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, was re-pressing, whereby the clay was processed in stiff-mud machines that extruded rigid clay which could be cut into blocks and molded. Because the clay would hold its shape well after molding, it could be re-pressed in a machine to create the crisp edges or designs. Kummel notes that this process was employed by a number of face-brick factories in New Jersey.[33] The stiff-mud process required the bricks to be dried before they were fired.[34] Among some of the options for drying bricks were open brick sheds or dryers. The Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company had two large brick sheds and a one-story dryer building. When the bricks were ready, they were fired in one of the company’s four bottle-shaped kilns.[35] Red burning clays for face brick were fired to cones 1 or 2, while buff burning clays were fired to 7 or 8.[36] The Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company originally produced bricks in six different colors: red, cream, buff, pink, brown, and gray, but by 1917 cream and pink had been dropped from the production line.[37] Once the bricks were ready for shipment, they were packed in barrels with hay and sawdust and sent to a shipping building on the main line of the railroad.[38] To ensure proper installation, the company provided its customers with architectural scale drawings and directions so that “any intelligent brick-mason can easily set the mantels up.”[39]

The Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company was sold in 1919, and part of the property was used as a garbage dump that was, in later years, often frequented by local bottle collectors. By the late 1980s the site was badly overgrown, located in a wooded area that was bordered by a housing development to the south and the main line of the Raritan River Railroad to the north. The kilns and most of the factory buildings were long gone, and what remained was a tangled mess of bricks, concrete, and vintage garbage. Still discernible was a sidetrack from the main rail line to a coal trestle with concrete abutments and piers. Adjacent to the trestle was a square-shaped smokestack (fig. 9). In the 1990s, prior to redevelopment, we visited the site and observed several pits that had been dug as part of an environmental survey. The excavations had cut through a vast waster pile and what had been exposed was an immense quantity of decorative brick (fig. 10). The pits were approximately three to four feet deep and were packed with a jumbled layer of discarded face brick covered by a six-inch layer of topsoil. Within the excavation area a sample of the company’s products was evident (figs. 11, 12). During the following month, a healthy sampling of bricks was collected, and we managed to acquire almost every design example. Most displayed firing imperfections, notably the spalling of the rear portion of the brick from the decorative face. The color of the bricks collected conformed well to what the company advertised, varying from red to buff with one mottled gray example (fig. 13). Others with hues of red and buff may in fact have been over- or underfired examples that were simply discarded. Indeed, the enormous waster pile may speak to the considerable technical difficulties faced by the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, and the bricks show a variety of problems. Some were fused together, overfired, distorted, and spalled (figs. 14, 15). Others were underfired and split. All in all, the waster pile vividly illustrates all the problems brickmakers might encounter while producing face brick. Also noted was a marked brick with a stenciled factory label that reads “Philadelphia & Boston / Face Brick Company / [Main Office 165?] Milk [St?] / Boston Mass / Works / Milltown” (fig. 16). Another unusual find was what appears to be a test tile—a small rectangular tile with one rounded end that was pierced, perhaps to receive a wire (fig. 17). It measures roughly 4.5 inches long, 3 inches wide, and .5 inches thick. The site was redeveloped for residential housing. During the remediation process several feet of soil were removed and sifted, unearthing bricks that were placed into an enormous pile that measured approximately 15 feet high by about 100 feet long. We scoured the pile to collect any outstanding examples. In addition to the waster bricks, the kiln foundations were also uncovered.

The Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company was an important producer of face brick from the late nineteenth century to the first decades of the twentieth century. Although the company name insinuates the importance of the urban areas of Philadelphia and Boston, one can argue that the firm may owe its very existence to New Jersey and its clay. Central New Jersey was a significant producer of bricks, tile, and terracotta, and the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company was part of that ceramics story. The discovery and study of its enormous waster pile serves to remind us of central New Jersey’s important ceramics past.

1. Heinrich Ries and Henry Kummel, The Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey (Trenton, N.J.: MacCrellish & Quigley, 1904), p. 165.

2. George Cook, Report on the Clay Deposits of Woodbridge, South Amboy and Other Places (Trenton, N.J.: Naar, Day & Naar, 1878).

3. Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 132.

4. M. Lelyn Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware in Central and Southern New Jersey (Metuchen, N.J.: Associated University Press, 1988), p. 18.

5. Richard Veit, Skyscrapers and Sepulchers: A Historic Ethnography of New Jersey’s Terracotta Industry, Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1997.

6. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book of the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company (Boston: Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, 1895) [hereafter Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1895], p. 1.

7. Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association, Report of the Sixteenth Triennial Exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association (Boston: Mills, Knight, 1888).

8. Boston Architectural Club, Catalogue of the First Annual Exhibition of the Boston Architectural Club (Boston: Clipston R. Sturgis, 1890).

9. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book of the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company (Boston: Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, 1904) [hereafter Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904], cover.

10. Middlesex County Deeds, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company (grantee) Emma Warnsdorfer (grantor), 462:442.

11. Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 342.

12. Heinrich Ries and Henry Leighton, History of the Clay Working Industry in the United States (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1909), p. 110.

13. Ibid., p. 135; Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 221.

14. Frederick Deibert, Rails up the Raritan: A History of the Raritan River Road (Piscataway, N.J.: Railpace, 1983), p. 7.

15. Industrial Directory of New Jersey, The Industrial Directory of New Jersey (Camden, N.J.: S. Chew & Sons, 1912), p. 290; Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book of the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company (Boston: Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, 1917) [hereafter Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1917], p. 1.

16. Bureau of Industrial Statistics, Department of Labor, The Industrial Directory of New Jersey (Paterson, N.J.: New Printing Company, 1918); Middlesex County Deeds, Philadelphia and Boston Brick Face Company (grantor) Frances E. Edgar (grantee), (Volume 655, 1919), p. 338; Sheriff’s Sale, The Daily Home News, April 28, 1919; “The Daily Home News, Edgar Estate Buys Big Philadelphia Brick Co. Tract for $25,000 at Sale,” June 5, 1919.

17. Sanborn Map Company, Insurance Map of Milltown, New Jersey (New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1924); Mark Nonestied, Images of America: East Brunswick (Charleston, South Carolina, Arcadia Publishing, 1999), p. 100.

18. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904.

19. Ibid.

20. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1895, p. 1.

21. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, sketch 26.

22. Ibid., p. 1.

23. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1895, p. 1.

24. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, p. 1.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, p. 1.

29. Sanborn Map Company, Insurance Map of Milltown, New Jersey.

30. Ibid.

31. Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 230.

32. Ibid., p. 232.

33. Ibid., p. 222.

34. Ibid., p. 233.

35. Sanborn Map Company, Insurance Map of Milltown, New Jersey.

36. Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 222.

37. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1917, p. 1.

38. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, p. 1; Sanborn Map Company, Insurance Map of Milltown, New Jersey.

39. Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, p. 1.

Heinrich Ries and Henry Kummel, The Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey (Trenton, N.J.: MacCrellish & Quigley, 1904), p. 165.

George Cook, Report on the Clay Deposits of Woodbridge, South Amboy and Other Places (Trenton, N.J.: Naar, Day & Naar, 1878).

Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 132.

M. Lelyn Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware in Central and Southern New Jersey (Metuchen, N.J.: Associated University Press, 1988), p. 18.

Richard Veit, Skyscrapers and Sepulchers: A Historic Ethnography of New Jersey’s Terracotta Industry, Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1997.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book of the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company (Boston: Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, 1895) [hereafter Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1895], p. 1.

Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association, Report of the Sixteenth Triennial Exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association (Boston: Mills, Knight, 1888).

Boston Architectural Club, Catalogue of the First Annual Exhibition of the Boston Architectural Club (Boston: Clipston R. Sturgis, 1890).

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book of the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company (Boston: Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, 1904) [hereafter Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904], cover.

Middlesex County Deeds, Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company (grantee) Emma Warnsdorfer (grantor), 462:442.

Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 342.

Heinrich Ries and Henry Leighton, History of the Clay Working Industry in the United States (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1909), p. 110.

Ibid., p. 135; Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 221.

Frederick Deibert, Rails up the Raritan: A History of the Raritan River Road (Piscataway, N.J.: Railpace, 1983), p. 7.

Industrial Directory of New Jersey, The Industrial Directory of New Jersey (Camden, N.J.: S. Chew & Sons, 1912), p. 290; Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book of the Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company (Boston: Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, 1917) [hereafter Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1917], p. 1.

Bureau of Industrial Statistics, Department of Labor, The Industrial Directory of New Jersey (Paterson, N.J.: New Printing Company, 1918); Middlesex County Deeds, Philadelphia and Boston Brick Face Company (grantor) Frances E. Edgar (grantee), (Volume 655, 1919), p. 338; Sheriff’s Sale, The Daily Home News, April 28, 1919; “The Daily Home News, Edgar Estate Buys Big Philadelphia Brick Co. Tract for $25,000 at Sale,” June 5, 1919.

Sanborn Map Company, Insurance Map of Milltown, New Jersey (New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1924); Mark Nonestied, Images of America: East Brunswick (Charleston, South Carolina, Arcadia Publishing, 1999), p. 100.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904.

Ibid.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1895, p. 1.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, sketch 26.

Ibid., p. 1.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1895, p. 1.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, p. 1.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, p. 1.

Sanborn Map Company, Insurance Map of Milltown, New Jersey.

Ibid.

Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 230.

Ibid., p. 232.

Ibid., p. 222.

Ibid., p. 233.

Sanborn Map Company, Insurance Map of Milltown, New Jersey.

Ries and Kummel, Clays and Clay Industry of New Jersey, p. 222.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1917, p. 1.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, p. 1; Sanborn Map Company, Insurance Map of Milltown, New Jersey.

Philadelphia and Boston Face Brick Company, Sketch Book 1904, p. 1.